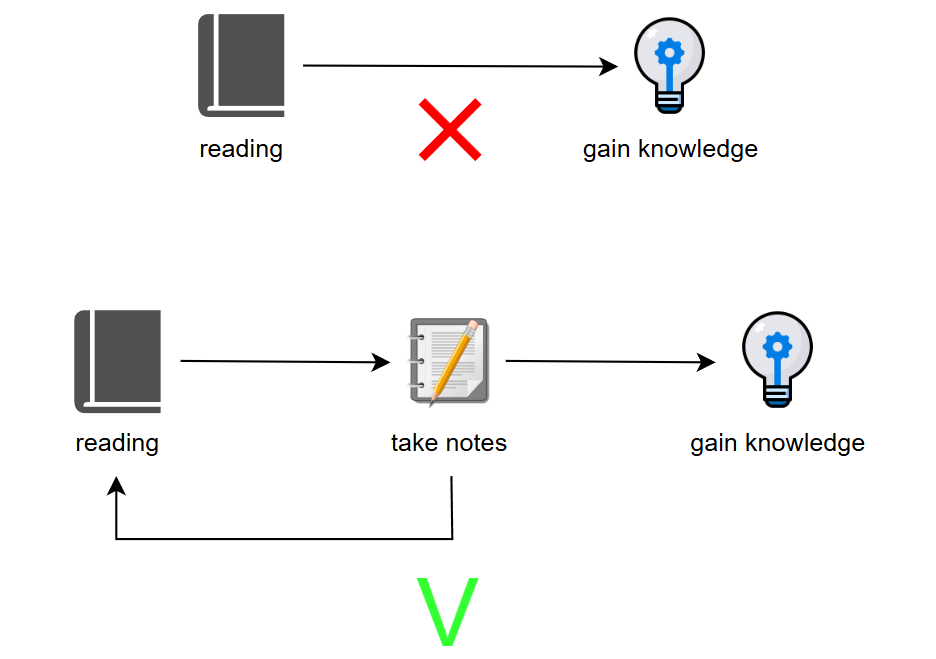

Online it’s easy to find dozens and dozens of articles titled ‘How to read a book’ that, in a superficial way, can be summed up with the phrase:

To read a book, it’s not enough to just read it.

This is true, especially when it comes to non-fiction books. Moreover, almost all the articles agree that it’s essential to ask yourself questions while reading and, most importantly, to take notes.

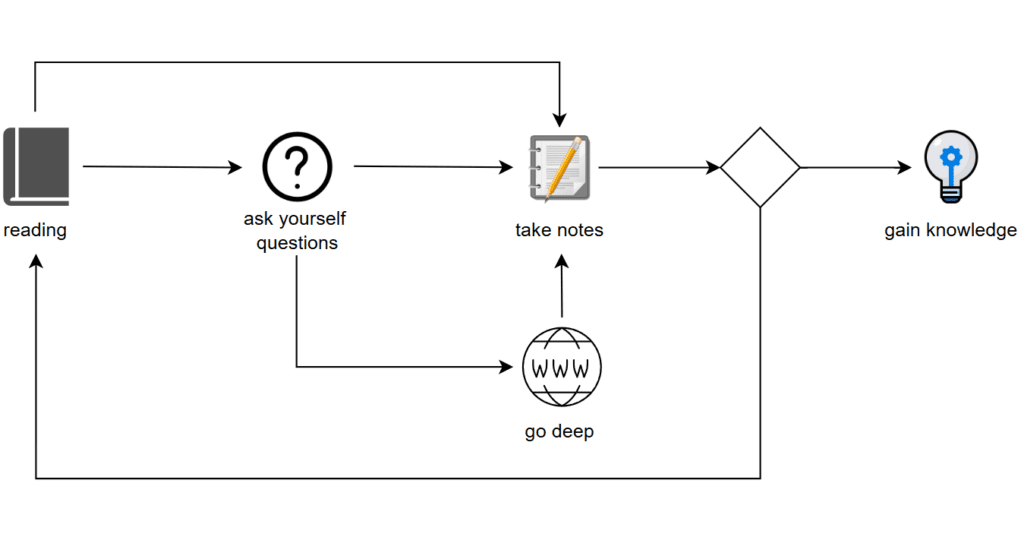

However, even this framework is a simplification of a process that involves many other layers, which depend on the complexity of the book as well as the level of understanding we wish to achieve (fully grasping the author’s message, delving into the themes discussed, questioning key passages and so on). Let’s look at this other flow:

It’s clear that as the complexity of the flow increases, the reading time will grow. This puts us in front of a problem: the number of books we can read in our lifetime is far more limited than it seems (and no, going back to the first flow is not a solution).

Before reading a book, it’s necessary to understand if it has any value for us and if it’s a good book (99% of them are not). How? There are several approaches:

- Book notes: you can explore notes or reviews from other readers to see if the book resonates with you. There are several blogs about this, such as those by Nat Eliason, Blas Moros and Derek Sivers (you can also find my notes on the books page);

- Superficial reading: read the book without focusing too much on details, completing an initial read-through. Then, revisit the key passages later;

- Listen to the author: look for interviews where the author discusses the book to get a better sense of its content and whether it’s right for you.

In this article, I want to explain how “I” read a book, as there is no universally recognised method, but I think it could be interesting to share the approach that works best for me.

I want to draw attention to the process of writing notes, which I consider the most critical part of reading. Without notes, it becomes impossible to organize ideas and fix concepts, let alone understand the author’s language.

For this process to be effective, it’s necessary to answer two questions: how and when.

How to take notes

Notes should capture key passages, not summarize the book. Overly long notes hinder both reading and later review.

The level of summary depends on the book’s complexity. The challenge is to be concise while retaining all essential information.

Notes aren’t just for processing your thoughts on what you’re reading but also to make them easily accessible in the future. For this reason, a good organizational structure is essential such as:

- Using an index: start with the book’s index and expand or refine it during your reading to retain only the most relevant concepts;

- Creating mind maps: identify the main themes and branch them out to a sufficient level of detail;

- Linking different note blocks: connect note sections when they share a logical or narrative relationship;

- Adding links to external resources: include references to resources used for deeper exploration during your reading;

- Writing open-ended questions: note unresolved points or doubts to explore later, either independently or by discussing them with others (perhaps in a book club).

It’s not always necessary to use all these tools, nor are they always effective for every book. Their use depends heavily on the type of book you’re dealing with and, most importantly, on the level of depth you want to achieve in exploring the topic.

Clearly distinguish between your own thoughts/interpretations and notes taken directly from the book. Focus on understanding the core problem the author addresses and their approach to resolving it throughout the chapters. This helps you keep the author’s original message clear, avoid misinterpretations.

Review your notes once completed, condensing them further where possible and expanding only if necessary.

When to take notes

Timing is likely the trickiest and most subjective part. The key question is: how often should you stop to process the information and make sure you haven’t missed anything?

The answer is far from simple. One approach could be to do it after each chapter or section but this would mean being completely dependent on the author’s pacing, which might not suit our own needs. If a chapter is very long, it can become difficult to note down thoughts and concepts from the beginning, sometimes making us go back and reread whole sections.

Personally, I find it better to use a system based on sub-concepts. A chapter often relies on several key ideas to convey its overall message, so using these as reading milestones has become my go-to approach for note-taking. I typically follow a structure like this:

- I underline key passages while reading to avoid frequent interruptions;

- If I find something that seems contradictory or unclear and that I consider important, I stop to think or explore other sources;

- When the author moves on to a different concept, I stop and take notes on what I’ve processed previously trying to be concise;

- I move on to the next concept.

After completing a chapter, I’ll often give my notes a quick once-over to fix any mistakes or condense repetitive ideas. Typically, I skip this step for subchapters or filler chapters with low added value.

The author’s language

Understanding the author’s language is key to interpreting their arguments and motivations behind them. This is essential for a meaningful analysis of the entire work.

This is how our writing process ensures we stay on track: when something seems off, taking the time to reflect and argue it helps us avoid superficial criticism and ensures that our analysis is well-founded.

Sometimes, an author may fail to fully develop their thesis or may force the narrative to fit their argument, leading to confusion or lack of clarity for the reader.

In such cases, asking questions can help us identify areas of disagreement and formulate constructive criticisms.

How to disagree

There’s a wonderful detailed article by Paul Graham that delves into this topic. More broadly, it’s essential to ask ourself:

- Disinformation: has the author presented incorrect or unreliable information to support their argument?

- Superficiality: does the author have a sufficient understanding of the topic or have important aspects been overlooked?

- Logical fallacies: are the facts accurate but the author’s reasoning contains contradictions?

- Incompleteness: has the author presented only one perspective or have they attempted to explore others, even arguing against those they don’t support?

Based on what we’ve agreed on, the only way to disagree is by providing our own arguments. The same points mentioned above should serve as a benchmark for the soundness of our reasoning.

Selective reading

Lastly, I want to quickly go over selective reading. We may not always be able to read books in their entirety (our resources are limited), but this does not necessarily pose a problem.

Especially with non-fiction books, it makes sense to focus on the sections that are particularly relevant at a given time in our lives, rather than reading the entire work.

By focusing on specific areas, we may sacrifice a complete understanding of the book, but as we’ve discussed, delving deeply is not always necessary. Instead, it is important to define what we want from the book and set our desired output in advance to get the most out of it.

Leave a comment on Telegram channel!